Youth Strength Training – Understanding Training Modes for Effective Training

Previously, we have discussed and stressed the importance of strength training and how regular strength training (1- 3 session per week) is essential for all athletes, especially youth athletes (15). From the potential link and development in the fundamental movement skills (5) to better health markers – e.g., insulin sensitivity (13), changes in body composition (21), and cardiovascular health (23). We know that an improvement in strength is a direct training outcome from regular and consistent bouts of strength training (freeweights, resistance machines, and bodyweight). Many mechanisms contribute to this new level of strength, for example, increase in efferent – central drive, motor unit recruitment, synchronization, rate coding (change in frequency or firing rate), morphological – changes in muscle size (9). Potentially, these mechanisms that aid in this new level of strength also help in motor performances (motor performances – improvement in a specific characteristic, for example, jump ability, agility, or sprinting) (1). This new strength level may also support in keeping the athlete robust – better coping strategies with high forces, minimising the risk of injury (especially lower limb injuries) (11).

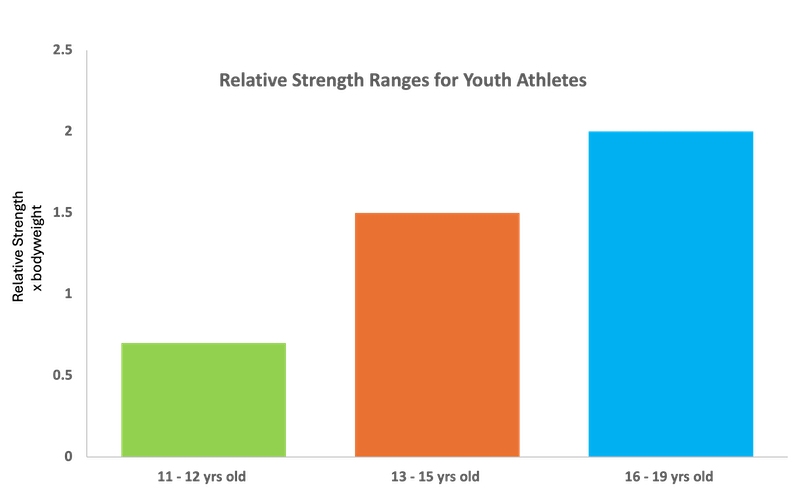

We’ve also discussed the importance of developing relative strength with youth athletes, as relative strength provides an excellent and valuable practical target, in conjunction with the athlete’s ‘age’ (chronological, biological, and training age) and long-term sporting demands. The expression trainability is often used and describes the sensitivity of adaptation relative to a given stimulus (sometimes challenging to directly measure due to the combination growth and maturation), for example, strength training, sprinting drills, or agility formats. Specifically, in strength training the different modes of training, freeweights, machine training, and bodyweight movement, alongside, repetitions, training volume, and frequency contribute to most of the training stimulus. We know that the trainability for relative strength is high for all athletes throughout their ages and in conjunction with maturation - ages - 11 – 12-years-old ~0.7 x bodyweight, 13 – 15-years-old ~1.6, and 16+ years-old ~2.0 x bodyweight (14). This reinforces the importance of frequently tracking the athlete’s physical developments (performance characteristics), as this will help coaches to make informed programme design decisions regarding the frequency of training, modes, loading protocols, and overall training volume.

Strength training quite simply is central within a long-term training plan (cannot be replaced or substituted). Coaches need to understand the significance that strength training plays in athlete preparation/performance, for all sports. Furthermore, as the mechanisms in the development of strength are highly trainable throughout the different ages, this also stresses the importance of starting strength training as early as possible (whenever the athletes have the maturity to follow clear instructions) (16).

Training Modes & Variables - Knowing Where or How to Start?

There are many effective modes of training that youth athletes can perform, including, freeweights – barbells, dumbbells, medicine balls, and kettlebells, fixed resistance machines, and bodyweight training (15). However, when selecting exercises, especially for new untrained athletes, there are some considerations.

Training age or experience - Normally, when starting strength training with youth athletes, their training age or experience is low (training age defined as, consistent years of strength training). If the athlete’s training age is zero (experience low), this classifies the athlete as untrained from a strength training perspective, thus the athlete will frequently gain strength from any mode of training – freeweights, resistance machines, or bodyweight training, as all training would fall into changes in neuromuscular function (10). Conversely, if the athlete has some experience in strength training, this needs to be considered, especially from a mode perspective. For example, two athletes with one-years strength training experience. The first athlete has trained with a range of freeweights, where the second athlete has trained solely on fixed resistance machines. It is central to understand that there is a learning aspect to strength training, especially from a long-term athlete development and transference to performance characteristics (19).

Training intensity – Regarding strength training (resistance training), training intensity is expressed as a percentage of the athlete’s one-repetition maximal (1RM or 100%). From testing the athlete’s strength level (1RM) or a projection of their 1RM, an effective load can be prescribed relative to the number of repetitions performed, for example – 8 repetitions = 80% 1RM, 10 repetitions = 75% 1RM, 20 repetitions = 60% 1RM. It is generally suggested that athlete’s start around 8 – 12 repetitions (50 – 70% 1RM) (17, 7). As the athlete’s develop their strength, training age (experience), the loading intensity can be progressed 80 – 100% 1RM, as this will drive further training adaptations.

| Training Experience | Beginner (untrained) | Intermediate | Experienced | Advanced (elite) |

| Volume (reps x sets) | 1 - 2 x 8 - 12 | 2 - 4 x 6 x 10 | 2 - 4 x 5 - 8 | 2 - 5 x 2 - 5 |

| Total number of exercises per session | 6 - 10 | 3 - 6 | 3 - 6 | 2 - 5 |

| Intensity (%1RM) | Bodyweight, 50 - 70% | 60 - 80% | 70 - 85% | 85 - 100% |

| Repetition Velocity (speed of movement) | Moderate - fast | Moderate - fast | Fast - maximal | Maximal |

| Rest Intervals (mins) | 1 | 1 - 2 | 2 - 3 | 2 - 5 |

| Frequency (sessions per week) | 2 - 3 | 2 - 3 | 2 - 4 | 2 - 5 |

| Recovery (hours between sessions) | 72 - 48 | 72 - 48 | 48 | 24 - 48 |

Table - from Llyod et al (2012). UKSCA Position statement: youth resistance training (17).

Training volume and frequency – simply, training volume refers to the amount of training completed (number of repetitions x number of sets), with the number of sets and repetitions having an inverse relationship, thus, an untrained athlete may start with 12 repetitions (~50% 1RM) for 1 – 2 sets, whereas a highly trained athlete (high training age) may be training at 4 – 5 repetitions (~80% 1RM) for 2 – 4 sets. Performing a high number of sets with high repetitions may place the athlete at risk of overtraining. Completing a high number of sets at a higher intensity (low repetitions) can be prescribed with a relatively low volume, plus, the athlete will need adequate exposure to higher loads to drive further strength adaptations as they progress and develop.

Training frequency is the number of training sessions completed per week. Studies comparing training frequency, especially with youth athletes are rare. In a meta-analysis of resistance training and performance in youth athletes, the study didn’t report any differences between 1, 2, and 3 sessions per week (15). Logically, untrained athletes could start with one-session per week, with a higher training frequency being prescribed as the athletes progresses through their athletic development. Conversely, training frequency can also be reduced to maintain their athlete’s strength level – depending on their sporting commitments. Generally, it is recommended that athletes average two strength sessions per week on non-consecutive days (15).

Are All Training Modes Equal?

Studies have clearly shown that youth athletes gain strength from freeweights, resistance machines, or bodyweight training, or a combination of the different modes, as long as appropriate and effective training intensity, volume, and frequency are applied (2, 4, 6, 8). However, it is strongly suggested or recommended that, if given the choice or the athletes have the opportunity, freeweights (barbells and dumbbell exercises, medicine drill, or kettlebell movements) should be selected and prescribed (15, 17). The rationale behind this thinking, is freeweights have been reported to recruit the prime movers (main muscle), synergists, and the fixators of the joint, compared to fixed machines/apparatus (18, 20, 22). Furthermore, there is a greater learning opportunity with freeweights, due to the range of motion (different planes of motion) and coordination, which may have a higher transference to sports performance (3).

Different modes of training - Lower body strength. Leg Press, bodyweight squat, barbell back squat.

Bodyweight training (press ups, pull ups) can be viewed similar to freeweights regarding the range of motion (planes of motion) and coordination, however, as no external load is prescribed, bodyweight training would be less demanding than freeweights (12). However, not all bodyweight exercises are the same.

From a practical application perspective, it would seem appropriate to start youth athletes (untrained), with bodyweight movements/exercises and then progress onto freeweights, or if the same movement (squat, lunges) start to add external load (change of intensity) as the athlete’s coordination and skill improves. This may be appropriate and effective for lower body musculature, especially if the athlete is extremely new to training – however, remember that athletes can start with low loads (~50% 1RM) in the squat, lunge, and deadlift; also getting athletes to practice with a range of equipment (trap-bar, barbell, dumbbells) will help the athletes to learn movement strategies, be aware of gym safety, and confidence – so the early the better!

When prescribing upper body strength exercises to new/untrained athletes, it may seem logical again to start with bodyweight training – press ups, chin ups, or pull ups. However, even though there is no external load, these movements may be too demanding, probably due to a general lack of strength (mostly coordination type qualities). Additionally, it is extremley challenging to alter the ‘load’ or intensity within bodyweight movements (for example, quantifying the intensity change from half press ups to full press ups, or assisted band pull ups to pull ups). Therefore, it may be more appropriate to start with upper body freeweight movements (dumbbell shoulder press, barbell bench press, dumbbell bench press), as the load can be easily managed, tracked, and logged (the athletes are exposed to an effective strength stimulus).

Through regular strength training sessions, the athletes will improve their coordination (inter/intra) and upper body weight training (press ups and chin ups) can be introduced. Again, due to the loading restrictions in the press ups, the exercise may return less adaptations now that the athletes have developed their general strength, however, the chin/pull can be further loaded and should be a foundational exercise throughout the athlete’s strength development.

Summary

Strength training is both an appropriate and effective mode of training for all athletes in preparation for their sports – improvements in performance characteristics, injury reduction, and overall athlete health and wellbeing.

The athlete’s training age and experience are significant, with new athletes being classified as untrained. There is an extensive library of exercises that can be prescribed using different modes – bodyweight training, fixed machines, and freeweights. All modes of training have shown to be effective in developing strength, however, freeweights are superior due to muscle recruitment and coordination strategies.

Bodyweight training can be used for lower body strength for untrained athletes, but it is recommended that freeweight exercises are prescribed as early as possible so that athletes can gain confidence with the equipment, learn gym safety, and start to record their training loads. Conversely, bodyweight-upper body strength exercises may be demanding for untrained athletes due to a lack of general strength and/or reduced muscle coordination – thus upper body freeweight exercises can be used (dumbbell shoulder press or bench press) so that the athletes can develop their general strength capacity and start their long-term strength training journey.

It is essential that athletes follow a programme with suitable training intensity and volume. Untrained athletes can start with a low intensity ~50%1RM (8 – 12 repetitions) for 1 – 2 sets of each exercise. The training intensity will increase (60 – 80% 1RM), as the athletes progresses their strength, skill, and experience. Training frequency is also an important factor with recommendations of 1 – 2 sessions per week, on non-consecutive days (average two sessions per week).

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Beringer, M., & Vom Heede, A. (2011). Effects of strength training on motor performances skills in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Paediatric Exercise Science, 23, 186 – 206.

- Chaabene, H., Lesinnski, M., Behm, D.G., & Granacher, U. (2020). Performance and health related benefits of youth resistance training. Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 1 – 10.

- Chelly, M.S., Fathloun, M., Cherif, N., Amar, M.B., Tabka, Z., & Van Praagh, E. (2009). Effects of back squat training program on lower power, jump, and sprint performances in junior soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning, 23(8), 2241 – 2249.

- Christou, M., Smilios, I., Sotiropoulos, K., Volaklis, K., Pilianidis, T., & Tokmakidis, S.P. (2006). Effects of resistance training on the physical capacities of adolescent soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 20(4), 783 – 791.

- Collins, H., Booth, J.N., Duncan, A., & Fawkner, S. (2019). The effect of resistance training interventions on fundamental movement skills in youth: a meta-analysis. Sports Medicine-Open, 5(17), 1 – 16.

- Dorgo, S., King, G.A., Candelaria, N., Bader, J.O., Brickey, G.D., & Adams, C.E. (2009). The effects of manual resistance training on fitness in adolescents. Journal of Strength & Conditioning, 23(8), 2287 – 2294.

- Faigenbaum, A.D., & Geisler, S. (2021). The promise of youth resistance training. Thieme, 37(02), 47 – 51.

- Faigenbaum, A.D., Milliken, L., Moulton, L., & Westcott, W.L. (2005). Early muscular fitness adaptations in children in response to two different resistance training regimens. Human Kinetics Journal, 17(3), 237 – 248.

- Folland, J.P., & Williams, A.G. (2007). The adaptations to strength training: morphological and neurological contributions to strength. Sports Medicine, 37(2), 145 – 168.

- Granacher, U., Puta, C., Gabriel, H.H.W., Behm, D.G., & Arampatzis, A. (2018). Editorial: neuromuscular training and adaptations in youth athletes. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 1 – 5.

- Hanlon, C., Krzak, J.J., Prodoehl, J., & Hall, K.D. (2020). Effect of injury prevention programs on lower extremity performance in youth athletes: a systematic review. Sports Health, 12(1), 12 – 22.

- Harrison, J.S. (2010). Bodyweight training: a return to basics. National Strength & Conditioning Association, 32(2), 52 – 55.

- Jan Van der Heijden, G., Wang, Z.J., Chu, Z, Toffolo, G., Manesso, E., Sauer, P.J., & Sunehag, A. (2010). Strength exercise improves muscle mass and hepatic insulin sensitivity in obese youth. Medicine Science in Sport & Exercise, 42(11), 1973 – 1980.

- Keiner, M., Sander, A., Wirth, K., Caruso, O., Immesberger, P., & Zawieja, M. (2013). Strength performance in youth: trainability of adolescents and children in the back and front squats. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(2), 357 – 362.

- Lesinski, M., Prieske, O., & Granacher U. (2016). Effect and dose-response relationships of resistance training on physical performance in youth athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50, 781 – 795.

- Lloyd, R.S., Cronin, J.B., Faigenbaum, A.D., Haff, G.G., Howard, R., Kraemer, W.J., Micheli, L.J., Myer, G.D., & Oliver, J.L. (2016). National strength and conditioning association position statement on long-term athletic development. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(6), 1491 – 1509.

- Lloyd, R.S., Faigenbaum, A.D., Mayer, G.D., Stone, M.H., Oliver, J.L., Jeffreys, I., Moody, J., Brewer, C., & Pierce, K. (2012). UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 26, 26 – 36.

- McCaw, S.T., & Friday, J.J. (1994). A comparison of muscle activity between free weight and machine bench press. Journal of Strength & Conditioning, 8(4), 259 – 264.

- Prieto-Gonzalez, P., & Sedlacek, J. (2021). Comparison of the efficacy of three types of strength training: body, weight training machines and free weights. Apunts Education, 145, 9 – 16.

- Schwanbeck, S., Chilibeck, P.D., & Binsted, G. (2009). A comparison of freeweight squat to smith machine squat using electromyography. Journal of Strength & Conditioning, 23, 1 – 4.

- Sgro, M., McGuigan, M.R., Pettigrew, S., & Newton, R. (2009). The effect of duration of resistance training interventions on children who are overweight or obese. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(4), 1263 – 1270.

- Spennewyn, K.C. (2008). Strength outcomes in fixed versus free-form resistance equipment. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(1), 75 – 81.

- Stricker, P.R., Faigenbaum, A.D., & McCambridge, T.M. (2020). Resistance training for children and adolescents. American Academy of Pediatrics, 145(6), 1 – 13.