The Importance of Testing and Monitoring Your Athletes

Usually, a training programme is designed and set for a block of training, for example 6 – 8 weeks (15). The training programme might be quite narrowly focused, high-frequency of strength exercises to improve maximal or relative strength, or the training programme might have different modes- strength training, plyometrics, and sprint drills to drive a cascade of physical qualities. Within that time the athlete will practice the movement or drills. Relative to the type of training, the athlete will adhere to the overload principle through effort/intensity, for example, if the training is trying to develop or maintain acceleration in sprints, the athlete will monitor their 5m, 10 or 20m times, with the aim to be consistent or even beat their time and capture a personal best. Moreover, if the training has a strength aim, the athlete will monitor their load-repetition relationship (and potentially RPE). Through the weeks, if the exercise load becomes too easy, i.e., the athlete can complete more repetitions using their starting training load, and/or their RPE drops, meaning that they have more repetitions in reserve, the athlete is advised to increase their load - with small increments being effective (0.5lb) (9). An increase in load will keep the athlete at the prescribed repetition range, and over the block of training, the athlete has adhered to the overload training principle.

Even though the training programme has a specific aim, which has been calculated by the coach, there’s no way of knowing if the training programme will hit or capture that specific fitness quality. Remember that most, if not all, fitness training prescription is based on guidelines relative to a mode and/or population, for example – general athletes (14), youth (11), active females (5). Because of the nature of the human body, no physical quality (strength, speed, mobility, hypertrophy) can be trained in isolation, so when a training programme is prescribed, and the athletes perform that training programme at a given frequency per week, coaches should expect individual differences in responses and adaptations.

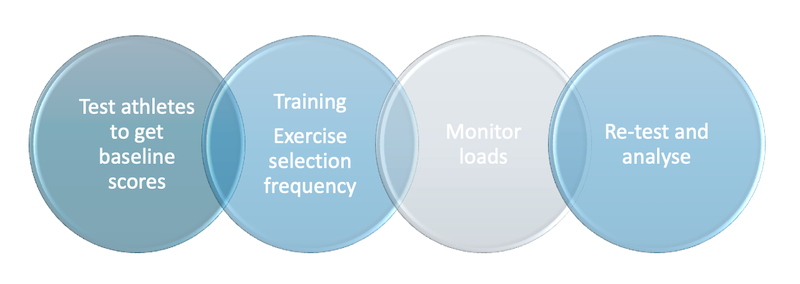

Testing, Monitoring, & Re-testing is a Part of the Training Cycle

Therefore, it is good coaching practice, if not essential, that coaches baseline their athletes using a set of tests or a test battery. Testing/baselining the athlete’s physical capabilities and then monitoring their training loads help to analyse how they adapted to that block of training. This, therefore, also informs the coach and helps them to steer the athlete’s next block of training from a theme or mode – i.e., strength training, plyometric, or sprint type drills, and/or perhaps, training dosage – intensity, frequency and/volume. Coaches need to appreciate and understand that testing, monitoring, re-testing, and analysing their findings is a part of the training cycle. Furthermore, from collecting the training data, this supports guided feedback (developing confidence and trust) to the athlete which will reduce the risk of overtraining and burnout that normally leads to injury/dropout.

Selecting Your Tests & Keeping Your Testing Consistent. Don’t Let Equipment be a Barrier. Field-Based Tests – Have Good Validity & Reliability

When selecting individual tests that create a test battery, it is important that the coach considers both the validity and reliability of each test (12). Validity refers to the specific nature of the test and does the test measure what it claims to measure. On the other hand, reliability refers to how repeatable the test is. If the test has a high reliability score, this will reduce the 'noise' within the test allowing the coach to make more meaningful decisions regarding the athlete’s test result and long-term development. Furthermore, the coach should also consider the athlete’s training age/maturation, experience, skill-level, and environment. It is not completely necessary to have high-tech equipment, for example, speed-gates or force-plates, as the cost of the equipment may be a barrier for many clubs, schools, and organisations. Many tests that have high validity and reliability can be delivered in the field (field-based tests) and are appropriate for youth athletes, and younger participants (1).

Examples of field-based tests include Yo-Yo test for football and other intermittent sports (2). 20m sprint test (8), with shorter distances measuring acceleration. Countermovement jump (10). Squat strength test relative to a 1RM (7), and Agility test (13). The above tests would create an effective test battery that would monitor the athlete’s physical development. Clearly, each test has considerations to reduce the noise and boost reliability. It is important that the coach follows their own procedures to keep the reliability high - for example, athletes are fresh and motivated, test order, recovery times between the efforts and test, and what is being recorded i.e., the best/highest score or average of the efforts. It is noteworthy to comment on strength testing, especially for younger or inexperienced athletes (low training age). The back squat is frequently used due to being a multi-joint exercise that recruitments major muscle groups. However, with youth and/or inexperienced participants it is recommended that they go through a familiarisation schedule to learn the exercise and to develop their skill and coordination. Again, this will increase both the validity and reliability of that test element.

| Test | Equipment | What it is Measuring | Considerations |

| 20m Sprint Test |

Open flat space, cones, stop watch | Acceleration | Error margin within using a stop watch. |

| Countermovement Jump | Clear wall, tape measure, and chalk | Power | Utilising the arms to initiate the SSC. |

| Squat Test (1RM, 3RM, 5RM) | Barbell, rack, plates, helpers | Strength | Familiarisation of the exercise. Improve the participant’s skill before testing. |

| Agility | Open flat space, cones, stop watch | Agility | Mostly assessing change of direction. Minimal decision-making qualities. |

The Importance of Data Capture and the Monitoring of the Athlete’s Physical Development

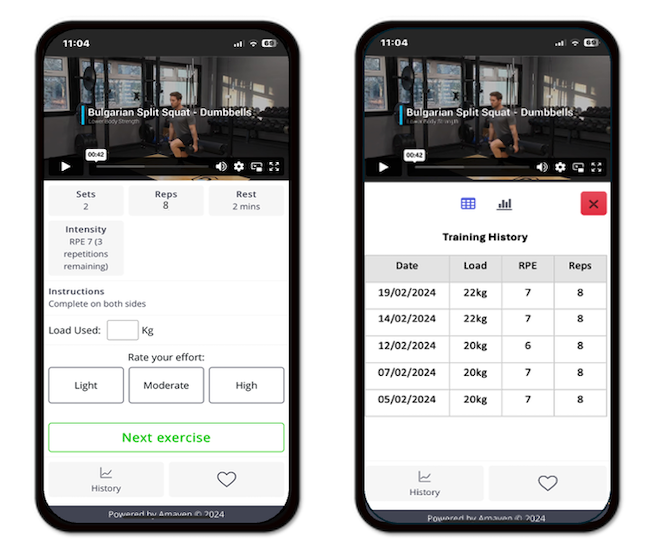

Completing a series of tests to set a baseline of the athlete’s physical capabilities is the first step in the training cycle. It is also essential that the athletes follow the training programme – exercise and frequency and the stick to the acute variables – loads-repetitions, sets, and rest periods. As previously mentioned, a major factor within the training programme is that the athlete tracks their training load (overload training principle). For example, the athlete is performing single-leg squats, repetition range of 8 (~80% 1RM) – RPE (8) – 2 repetitions in reserve to keep the skill level consistent. The athlete starts their training using 20kg, as this is providing a level of stimulus to the muscular system. With optimal training and rest, the athlete may be able to perform more repetitions than the desired 8-repetitions. At this point, the athlete should increase the load and return to completing 8-repetitions. The smaller the increment in load, is potentially more effective, as the athlete’s technique will not be comprised. By monitoring the load-repetition relationship, the athlete has obeyed the overload training principle, which will drive both neurological and muscular adaptations. Improvements in strength are mostly linear, but fatigue, nutrition, outside factors - wellbeing will affect weekly training sessions.

With the development of technology, it is now easy to capture the athlete’s training data. Our app has been especially created to help all athletes in their training and physical development. The athletes can watch the exercise to learn and practice their technique. The acute variables – repetitions, sets, rest, and RPE are clearly displayed. The athlete then selects their training load and uploads, to power their training history. On revisiting that exercise on their next training session, the athlete can review their past training loads, making their training significantly more effective.

Feedback to Athletes, Sport Coaches, & Parents – Detailed Athlete Reports Created Simply & Quickly

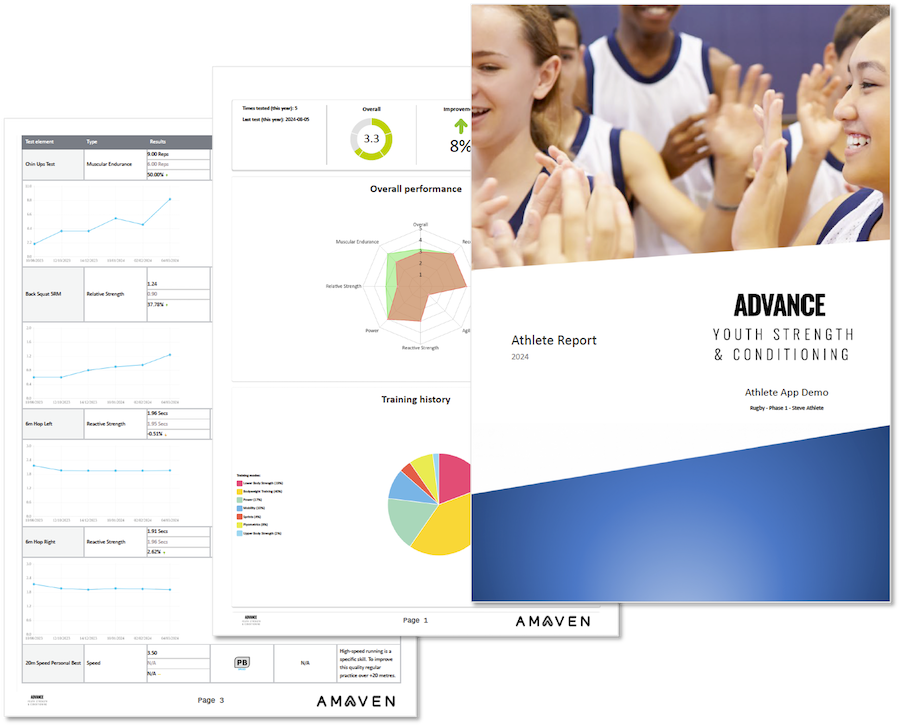

The latter part of the training cycle, is to re-test, compare, and analyse the block of training. This is only possible if the first steps are completed well – testing/baseline of the athlete’s physical capabilities – the athletes following the training and monitoring of their training loads. After re-testing the athletes, this empowers the coach to analyse any differences relative to a set goal or sporting demand.

Strength and conditioning is universal within academies and high-profile teams. Youth strength and conditioning is picking up pace, especially in high-schools and sport clubs, but more emphasis is required on the importance of athletic development and athletic preparation, as both are highly linked with injury reduction (3, 4, 6). Therefore, by following an effective training cycle – test – training – monitor loads – re-test – a detailed athlete report can be created and shared with key personnel (sport coaches and parents). This creates an ideal opportunity to offer feedback to the athlete, making their training athlete-centred, as the athlete will feel supported and recognised – boosting their motivation and confidence. It is also a great opportunity to offer support, feedback, and expertise to sport coaches (identify sporting needs, position, if youth athlete – maturation consideration), and to parents – as strength and conditioning can benefit all youths in their desire to improve their physical development for sport readiness, health, and overall wellbeing.

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Artero, E.G., Espana-Romero, V., Castro-Pinero, J., Suni, J., Castillo-Garzon, M.J., & Ruiz, J.R. (2011). Reliability of field-based fitness tests in youth. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 32, 159 – 169.

- Bangsbo, J., Iaia, F.M., & Krustrup, P. (2008). The yo-yo intermittent recovery test – a useful tool for elevation of physical performance in intermittent sports. Sports Medicine, 38(1), 37 – 51.

- Bank, N., Hecht, C., Karimi, A., El-Abtah, M., Huang, L., & Mistovich, R.J. (2022). Raising the youth athlete: training and injury prevention strategies. Journal of POSNA, 4(2), 1 – 13.

- Coughlan, D., & Ward, N. (2017). England’s golf’s physical preparation programme, implemented for the under-16 regional elite golf players. Professional Strength & Conditioning, 46, 28 – 34.

- Fernandez-del-Valley, M., & Naclerio, F. (2023). Resistance training guidelines for active females throughout the lifespan, from childhood to elderly. The Active Female, 463 – 482.

- Gamble, P. (2008). Approaching physical preparation for youth team sports players. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(1), 29 – 42.

- Grgic, J., Lazinica, B., Schoenfield, B.J., & Pedisic, Z. (2020). Test-retest reliability of the one-repetition maximum (1RM) strength assessment: a systematic review. Sports Medicine – Open, 6(31), 1 – 16.

- Hopker, J.G., Coleman, D.A., Wiles, J.D., & Galbraith, A. (2009). Familiarisation and reliability of sprint test indices during laboratory and field assessment. Journal of Sports Sciences & Medicine, 8, 528 – 532.

- Hoster, D., Crill, M.T., Hagerman, F.C., & Staron, R.S. (2001). The effectiveness of 0.5-lb increments in progressive resistance exercise. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 15(1), 86 – 91.

- Jimenez-Reyes, P., Samozino, P., Pareja-Blanco, F., Conceicao, F., Cuadrado-Penafiel, V., Gonzalez-Badillo, J.J., & Morin, J. (2016). Validity of a simple method for measuring force-velocity-power profile in countermovement jump. International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance, 12(1), 36 – 43.

- Llyod, R.S., Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D., Stone, M.H., Oliver, J.L., Jeffreys, I., Moody, J., Brewer, C., & Pierce, K. (2012). UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 26, 26 – 39.

- McGuigan, M.R., Cormack, S.J., & Gill, N.D. (2013). Strength and power profiling of athletes: selecting tests and how to use the information for program design. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 35(6), 7 – 14.

- Monica, M.Y., Gerard, M., Bishop, C., & Gonzalo-Skok, O. (2022). Assessing the reliability and validity of agility in team sports: A systematic review. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 36(7), 2035 – 2049.

- Pearson, D., Faigenbaum, A., Conley, M., & Kraemer, W.J. (2000). The national strength and conditioning association’s basic guidelines for resistance training of athletes. National Strength & Conditioning Association, 22(4) 14 – 27.

- Tan, B. (1999). Manipulating resistance training program variables to optimise maximum strength in a men: a review. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 13(3), 289 – 304.