Readiness to Perform - Monitoring Wellbeing & Recovery

Being ready to perform, both in training and in sport, requires a balance between training stress, or a given stimulus, and recovery. Failure to achieve this balance will possibly lead to a chronic fatigued state and overtraining or non-functional overreaching (19, 20). Undoubtedly, the health and wellbeing of youth athletes is a bedrock principle within the National Strength and Conditioning view on long-term athletic development and is stressed throughout their pillars of success (10). Furthermore, they and others highlight the importance and integration of developing both skill-related and health related fitness (17), along with clear monitoring tools – to track the athlete’s development, as this helps in reporting, communication, support and feedback, and setting targets – within lifestyle, training frequency and loads, and sport practice/competition.

When it comes to youth sport, unfortunately, we may be falling short, extremely short of the mark in preparation for sport (5) and monitoring overall athlete wellbeing. Clearly, sport is great vehicle for many reasons – social inclusion, specific fitness and skills, leadership and communication, however, there still seems to be a complete focus and mindset on winning, rather than developments in the athlete’s physical capacities and overall wellbeing. We need to prioritise the athlete’s wellbeing and their individual growth and maturation to minimise the risk of injuries and dropout (13, 14, 16).

The wellbeing of each athlete is clearly multifactorial, as there is no universal test that can capture all the different areas, just like testing the physical capacities a series of tests can help build an athlete profile – strength, acceleration, power, or agility. Simple but effective questionnaires have been used to help quantify wellbeing status – sleep quality, mood, fatigue level, appetite and muscle soreness (15), and recovery from training loads (8).

By enabling youth athletes to track both their daily wellbeing and recovery from training and sport competition, coaches can support and give guidance on individual loading protocols to reduce the risk of overtraining and non-functional overreaching. We know that there are strong associations and relationships between factors (see below) that may increase the risk of injury, burnout, or dropouts. By identifying these risks and monitoring, we can help our athletes to stay healthy and robust.

Potential Injury Risk Factors

- A lack of preparation – physical qualities are below recommendations relative to the demands of the sport

- Playing too much competitive sport or training to sport ratio – sport specialisation

- Using their sport as their physical training – sport specialisation

- High Training volumes and spikes in the training volume

- Accumulation of lifestyle ‘stressors’ - relationships, academic studies, exams, poor sleep quality routines, and nutrition – low nutrient quality

Youth athlete’s schedules can be demanding, and training volumes can be problematic leading to states of overtraining. An example of high training volumes in youth athletes can be seen in a study exploring the work demands (athletic – track and field) in different age groups 13 – 14-year-olds, 15 – 16-year-olds, and 17-year-olds in athletic athletes. 78.6% of the athletes reported an injury, with the average time loss of ~3 weeks with most (76%) of the injuries being classified as overuse. Furthermore, 17.3% of the athletes retired or dropped out of sport due to their injuries before the age of 18. The authors of the study suggested that coaches should monitor the athlete’s training schedule, intensity, and weekly loads to help to minimise injuries (7). Additionally, lifestyle factors should be considered, especially within adolescent athletes, as they need to balance many different areas – relationships, academic studies, exams, sleep patterns, screen-time. It is highly recommended that youth athletes complete and record their training using training diary or journals – as this can help with tracking and monitor of training loads, energy-freshness status, and overall trends (11).

Using Technology to Track Wellbeing & Recovery

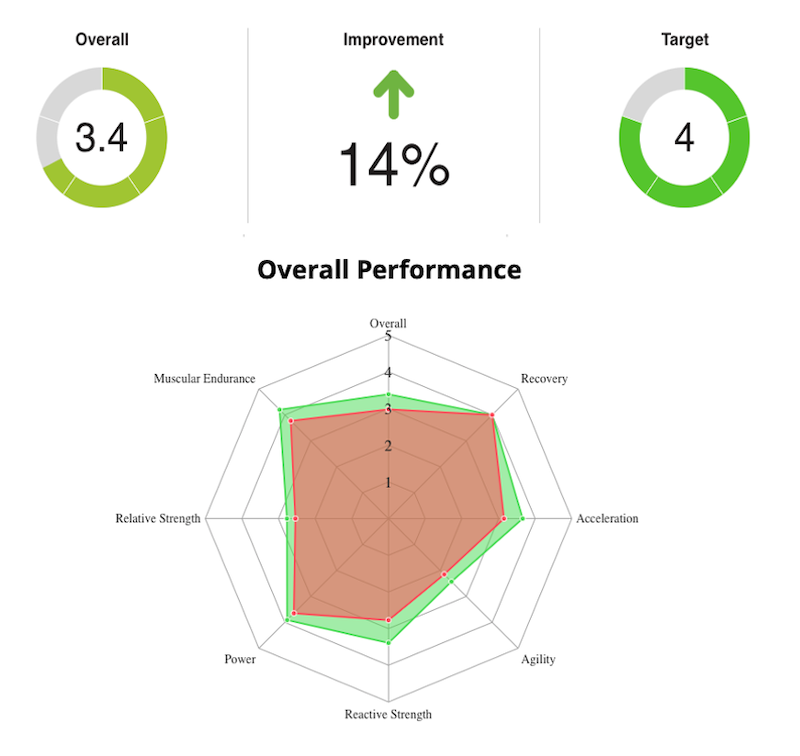

With the help of technology, it is now possible to simply track a range of athlete variables, including training loads (loads lifted), repetitions completed, along with sets – training volume. Number of sprints, distance covered, and rest times, with an RPE level to qualify an exertion level, along with wellbeing scores and recovery levels. This information is both powerful and valuable, as it builds a training history for each athlete and helps to track the athlete’s readiness/freshness for training or competition.

For example, athletes can regularly complete their wellbeing questionnaire (sleep patterns, freshness, appetite, level of soreness) and their level of recovery. This can be delivered back to the athlete using red, amber, and green days. A Red day = wellbeing is low, potentially from lack of sleep, or energy levels. The athlete is not fully recovered from their previous training session. Suggestions to the athlete could be to take an active recovery day, and focus on lifestyle - sleep, hydration, and nutrition. An Amber day = some tiredness or fatigue or just don’t feel on it. Wellbeing ok, but again, not optimal, and not fully recovered. Suggestions could be, consider the training volume. Complete 1 set rather than 3 sets. Finally, a Green Day – feeling fresh, good to go. Feeling motivated and fully recovered. Training suggestions - Time to work hard, full intent in the lifts, sprints, or plyometrics.

| Freshness Rating | Description/Feeling | Training Considerations or Suggestions |

| Red | Tired, fatigued, lack of motivation. | Take it easy, skip the session for a light active recovery session/activity - walk in the park. Focus on nutrition, sleep pattern, and rest. |

| Amber | Slightly tired, some soreness, low on energy. | Be mindful that you are not fully recovered. Reduce the training volume, complete 1 set per exercise rather than 2 or 3 sets. |

| Green | Feeling fresh and well recovered. Highly motivated and lots of energy. | Fresh and ready to go. Time to train 'hard' but remember that quality is key. Full intent in your lifts, plyometrics, or sprint drills. |

Internal and External Measurements

When asking athletes to track their wellbeing, recovery status, and training variables, these are a collection of both internal and external measurements or load (we must be careful with using the term load, as load has a clear definition from a mechanical perspective). Generally, external ‘load’ measurements are more objective, or calculated as work completed by the athlete, for example number of sprints, acceleration, jumps – contact times, to training volume (3). Internal measurements ‘load’ are associated with physiological, heart rate, lactate levels, but also include psychological exertion level, typically based on the Rate of Perceived Exertion scale 1 – 10 (1).

The Rate of perceived exertion (RPE), is frequently used to capture exertion levels, normally based on a 1 – 10 scale (1 – being light or easy, to 10 being max, or very hard). It has been reported that using RPE-related measures or values with youths should be done carefully, as youths may not be able to self-assess their training effort – this is true with all untrained or beginners starting their training journey, but their perception of effort will become consistent with practice and experience – so the sooner it is implemented the quicker the athletes can start to reflect and learn.

| Type | Description | Examples |

| Internal | Physiological and/or psychological |

Heart rate |

| Exernal | Work completed by the athlete | Power output Load lifted Training Volume (reps x sets) Total training volume (load x reps x sets) Contacts - jumps and plyometrics Number of sprints Distance covered |

Even though the Loads have been categorised, as either Internal or External, Load should be viewed as a combination of internal and external factors, as they are fully integrated and help coaches to monitor which elements may be affecting the readiness (fitness) of the athlete. Please remember that an identical strength training session, same exercises, loads and rest periods (external load) will be experienced differently by the same athlete on different days (internal load). Furthermore, the same strength session will also be experienced differently by a range of athletes, due to their training age, training level, nutrition, sleep, and fatigue status. Thus, athletes that start to track their wellbeing, recovery status, and training loads are considering both internal and external factors, which will aid in long-term performance and minimising injury or overtraining – readiness to train or perform.

Athlete Centred Approach

By taking an athlete centred approach, the athlete’s training will organically become more individualised, as their training session will be based on their wellbeing and recovery status – this will reduce the risk of overtraining and burnout. It seems that burnout, overtraining, which may lead to illness and/or injury are all linked to fatigue, accumulation of fatigue (chronic), with the athletes not being able to fully recover. However, we need to appreciate that there’s no good or bad, relative to load, as the optimal dosage of load is required to drive fitness adaptations – thus low load could lead to under preparation and high load could lead to chronic fatigue. High loads may not be a problem if the athletes are healthy and resilient, it may be more problematic if there are sudden changes in Load or ‘spikes’ which increase the risk of illness or injury (4).

Furthermore, as youth athletes are at risk of developing a sport-related injury, with knees, and lower back being the most common sites of injury (9). Young female athletes are more at risk of sustaining an ACL-type injury (anterior cruciate ligament) than male athletes (18). With additional risk factors being highlighted regarding ACL injuries, including, structural differences, hormonal changes through menstrual cycle, joint laxity, knee stiffness and neuromuscular patterns (6). Therefore, enabling young females to track their readiness and to train (exertion level) relative to their wellbeing score and recovery status, logically this will aid in their overall health, wellbeing, robustness – minimising lower limb injuries.

Summary

We have a responsibility to help and support youths to be healthy first and athletes second, remember that athlete development is a long-term project. By educating and supporting athletes to track their wellbeing scores and recovery status, this will help with overall readiness to train and perform – reducing the risk of overtraining and nonfunctional overreaching. With the use of technology, this aids in individualising strength and conditioning programmes, as athletes become more reflective and intuitive, making positive decisions in their training (fitness), along with optimal lifestyle choices and effective recovery strategies (accumulation of fatigue). Technology also helps the coach in offering long-term support, guidance, and feedback, which will clearly increase the athlete’s confidence, resilience, and sporting performances.

As the International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement States (2).

Create guidelines for a sustainable model to develop healthy, resistant, and capable youth athletes, while providing opportunities for all levels of sport participation and success.

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Assis Manoel, F., Melo, B.P., Cruz, R., Villela, C., Alves, D.L., Da Silva, S.F., & De Oliverira, R. (2016). The utilisation of perceived exertion is valid for the determination of the training stress in young athletes. Journal of Exercise Physiology, 19(1), 27 – 32.

- Bergeron, M.F., Mountjoy, M., Armstrong, N., Chia, M., Cote, J., Emery, C.A., Faigenbaum, A., Hall, G., Kriemler, S., Leglise, M., Malina, R.M., Pensgaard, A.M., Sanchez, A., Soligard, T., Sundgot-Borgen, J., van Mechelen, W., Weissensteiner, J.R., & Engebretsen, L. (2015). International Olympic committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49, 843 – 851.

- Bourdon, P.C., Cardinale, M., Murray, A., Gastin, P., Kellmann, M., Varley, M.C., Gabbett, T.J., Coutts, A.J., Burgess, D.J., Gregson, W., & Cable, T.N. (2017). Monitoring athlete training loads: Consensus statement. International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance, 12, 161 – 170.

- Gabett, T.J. (2017). The training – injury prevention paradox; should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50, 273 – 280.

- Gamble, P. (2008). Approaching physical preparation for youth team-sports players. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 30(1), 29 – 42.

- Huston, L.J., Greenfield, M.V.H., & Wojtys, E.M. (2000). Anterior cruciate ligament injures in the female athlete: Potential risk factors. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research, 372, 50 – 63.

- Huxley, D., O’Conner, D., & Healy, P.A. (2013). An examination of the training profiles and injuries in elite youth track and field athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 14(2), 185 – 192.

- Laurent, M.C., Green, M.J., Bishop, P.A., Sjokvist, J., Schumacker, R.E., Richardson, M.T., & Curtner-Smith, M. (2011). A practical approach to monitoring recovery: development of perceived recovery status scale. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(3), 620 – 628.

- Leppenan, M., Pasanen, K., Kannus, P., Vasankari, T., Kujala, U.M., Heinonen, A., & Parkkari, J. (2017). Epidemiology of overuse injuries in youth team sports: A 3-year prospective study. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 38(11), 847 – 856.

- Lloyd, R.S., Cronin, J.B., Faigenbaum, A.D., Haff, G.G., Howard, R., Kraemer, W.J., Micheli, L.J., Myer, G.D., & Oliver, J.L. (2016). National strength and conditioning association position statement on long-term athletic development. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(6), 1491 – 1509.

- McFarland, M., & Bird, S.P. (2014). A wellness monitoring tool for youth athletes. Journal of Australian Strength & Conditioning, 22(6), 22 – 26.

- Merkel, D.L. (2013). Youth sport: positive and negative impact on youth athletes. Journal of Sports Medicine, 151 – 160.

- Paterno, M.V., Taylor-Haas, J.A., Myer, G.D., & Hewett, T.E. (2013). Prevention of overuse sports injuries in the young athlete. Orthop Clin North Am, 44(4), 553 – 564.

- Rejeb, A., Johnson, A., Vaeyens, R., Horobeanu, C., Farooq, A., & Witvrouw, E. (2017). Compelling overuse injury incidence in youth multisport athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 495 – 502.

- Sawczuk. T., Jones, B.L., Scantlebury, S., & Till, K. (2018). Relationships between training load, sleep duration, and daily wellbeing and recovery measures in youth athletes. Paediatric Exercise Science, 30£3), 345 – 352.

- Stein, C.J., Micheli, L.J. (2010). Overuse injuries in youth sports. The Physician and Sports Medicine, 38(2), 102 – 108.

- Stodden, D.F., Gao, Z., Goodway, J.D., & Langendorfer, S.J. (2014). Dynamic relationships between motor skill competence and health related fitness in youth. Paediatric Exercise Science, 26, 231 – 241.

- Toth, A.P., & Cordasco, F.A. (2001). Anterior cruciate ligament injures in the female athlete. The Journal of Gender-specific Medicine, 44(4), 25 – 34.

- Williams, C.A., Winsley, R.J., De St Croix, M.B., & Lloyd, R.S. (2017). Prevalence of non-functional overreaching in elite male and female youth academy football players. Science & Medicine in Football, 1(3), 222 – 228.

- Winsley, R., & Matos, N. (2011). Overtraining and elite young athletes. Medicine Sport Science, 56, 97 – 105.