Monitoring Youth Athletes & Physical Preparation for Youth Sport

Most sports are extremely dynamic, (netball, hockey, tennis, and football to name a few), which requires the athletes to be able to repeatedly jump, hop, accelerate, complete high-speed sprints and to change direction at speed (2, 17, 18). Collectively, these physical qualities are known as the specific sporting demands. The sporting demands will be different from sport to sport, and position. For example, in youth netball, within a 60-minute game, players perform a series of high-anaerobic bursts of hops and jumps, along with performing up to 80, very short (4 – 6 seconds), maximal sprints (9). Another example is in youth football, where a study examined the total distance covered, and the different types of running speeds. Player position did dictate the demands, with midfield players covering the highest distances along with skill movements. Attackers completed a greater number of high-speed runs compared to defenders (11). It is, therefore, essential that sport coaches and PE teachers review and appreciate that sports and positions have different demands, and by monitoring key metrics along with their physical development, we can get our youths – Sport Ready – improve sports performance and reduce the risk of injury.

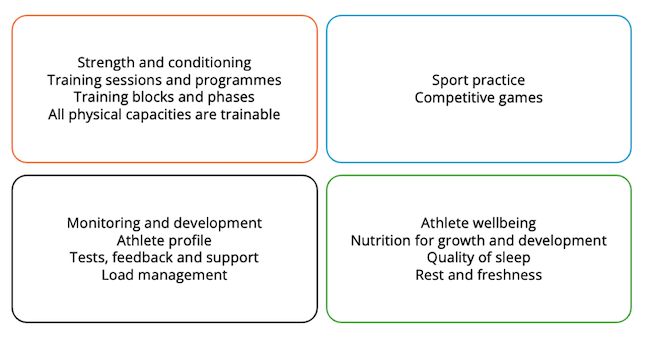

Understanding the sporting demands and physical preparation falls into a long-term athletic development model. A long-term athlete development model can be viewed into four areas. (a) Strength and conditioning – training sessions and programmes, phases, and blocks of training. (b) Performance - sport practice and competition. (c) Monitoring and tracking of the athlete – strength and conditioning tests, athlete profile, feedback, support, and load management. (d) Athlete wellbeing – optimal nutrition, quality of sleep, and recovery – to reduce the risk of injury.

Testing and Monitoring of Youth Athletes

Testing and monitoring of youth athletes is starting to become more common and recommended (1, 8, 14) as there are many benefits in regular testing, including monitoring the athletes physical development, it provides an opportunity for athletes to set themselves goals, sets the importance of performing regular strength and conditioning training, helps the coach with support and feedback, and can potentially aid in reducing overtraining and injuries (3).

There are many field-based physical performance tests to choose from, for example, countermovement jump, strength tests – back squats, pull ups, and press ups, different sprint distances, 5, 10, 20, and 30 metres, and different forms of shuttle runs – YoYo test, 20m-multistage test, and 300-yard shuttle. Athlete wellbeing and recovery scores are frequently captured in the forms of questionnaires (7, 15).

As previously mentioned, by regularly performing a set test battery, this will expose youth athletes to a range of skills, a philosophy of trying their best, it opens a communication pathway for the athletes to discuss their areas of development, points the athletes to set personal goals, and motivates the athletes to invest into their strength and conditioning training.

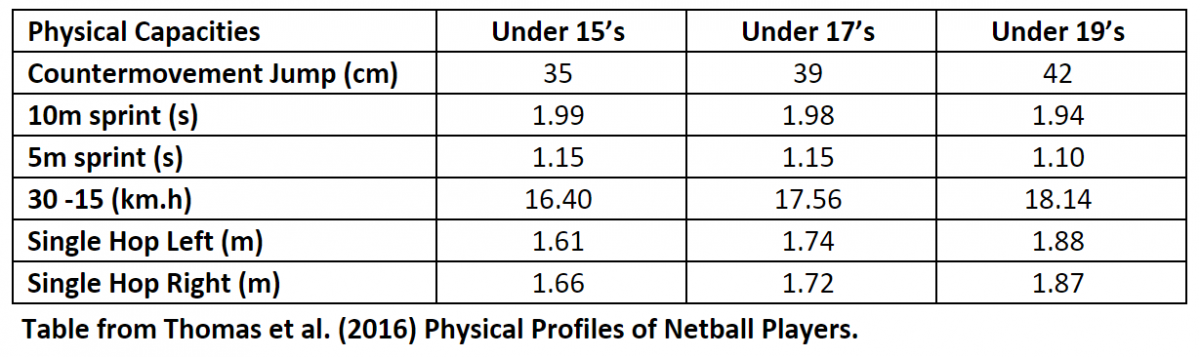

Testing and monitoring youth athletes can help to track their overall physical development. As the youth athlete’s physical capacities improve, along with their confidence and training experience, we can start to compare their physical capacities (vertical jump height, speed, and agility) to established athletes in a specific sport and even position. This is known as an athlete needs analysis. For example, in the below table of netball players, we can analyse their jump ability, acceleration (5 and 10 metre times), 30-15 times, and single leg hop performances. We can clearly see that the sporting demands increase with age, with a 20% difference in jump height from the under 15’s to the under 19’s age group.

Using established physical qualities at different ages helps to set a baseline and a goal for the athletes to work towards. This helps the athletes to meet the demands of the sport which will help with sport performances and reducing the risk of injury.

Strength and Conditioning

Unfortunately, general preparation for sport practice and competition is the most overlooked aspect of youth sport (5, 6, 12), with many athletes falling into sport specialisation, leading to overtraining and injury (13). The true benefit from testing and monitoring youth athletes, is that we can analyse where they are, and from their test scores, set them clear training and instructions to follow – a strength and conditioning programme.

According to the Youth Development Model (10), all physical capacities are highly trainable throughout the ages. Young athletes can start with bodyweight training, tag games, and a range of sprints, as this will develop a cascade of neuromuscular adaptations. At this early stage of development, it is worth noting that testing and training should be viewed holistically, with the emphasis placed on fun, engagement, and the athletes learning new skills.

As the young athletes grow and mature into adolescents (girls >11years old, boys >13years old) their strength and conditioning training can become more structured, for example, strength training, plyometrics drills, power training, agility, and sprint drills. Furthermore, the athlete’s test battery might be linked towards a specific sport or even position, but even so, the test scores should still be viewed holistically, along with other lifestyle factors – nutrition, recovery, and sleep. As the athlete develops their strength, power, muscle mass, coordination and speed, the athlete needs adequate sport practice to allow these new physical qualities to manifest into new sport-motor performances.

Summary

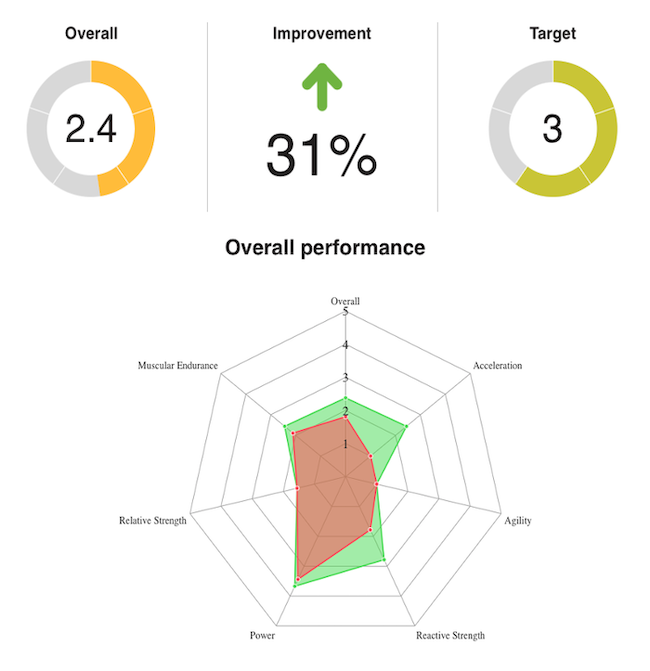

Working and coaching young and youth athletes with different training experiences, abilities, and needs, we recommend that each athlete completes a series of test elements, for example, 10 metre acceleration, pull ups, agility test, countermovement jump, and 5Rm back squat. The athlete's test results can be viewed and tracked. By completing the tests and regularly re-testing the athlete, this informs the coach of the athlete’s physical capacities and how the athlete is developing. It also helps the athlete to set personal goals and see progress, and most importantly, it highlights the importance of performing their strength and conditioning training and leading a healthy lifestyle.

An example of an athlete's test scores

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include -

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Barker, A.R., & Armstrong, N. (2011). Exercise testing elite young athletes. Medicine in Sports and Science, 56, 106 – 125.

- Bishop, C., Brazier, J., Cree, J., & Turner, T. (2015). A needs analysis and testing battery for field hockey. Professional Strength & Conditioning, 36, 15 – 26.

- Brink, M.S., Visscher, C., Arends, S., Zwerver, J., Post, W.J., & Lemmink, K.A. (2018). Monitoring stress and recovery: new insights for the prevention of injuries and illnesses in elite youth soccer players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44, 809 – 815.

- Davidson A., & Trewatha G. (2008). Understanding the Physiological Demands of Netball: A time-motion Investigation. International Journal Perform Analysis of Sport, 8, 1 – 17.

- Faigenbaum, A.D., MacDonald, J.P., & Haff, G.G. (2019). The American College of Sports Medcine, 18(1), 6 – 8.

- Gamble, P. Physical preparation for netball – Part 1: Needs analysis and injury epidemiology. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 22, 10 – 15.

- Hamlin, M.J., Wilkes, D., Elliot, C.A., Lizamore, A., & Kathiravel, Y. (2019). Monitoring training loads and perceived stress in young elite university athletes. Frontiers in Physiology, 10(34), 1 – 12.

- Heriques-Neto, D., Hetherington-Rauth, M., Magalhaes, J.P., Correia, I., Judice, P.B., & Sardinha, L.B. (2021). Physical fitness tests as an indicator of potential athletes in a large sample of youths. Scandinavian Society of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine, 1 – 8.

- Hopper, D.M., McNair, P., & Elliott, B.C. (1999). Landing in Netball. Effects of Taping and Bracing the Ankle. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 33, 409 – 413.

- Lloyd R.S., & Oliver J.L. (2012). The youth physical development model. A new approach to long-term athletic development. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34, 61 – 72.

- Lovell, T.W., Bocking, C.J., Fransen, J., Kempton, T., & Coutts, A.J. (2018). Factors affecting physical match activity and skill involvement in youth soccer. Science and Medicine in Football, 2(1), 58 – 65.

- Merkel, D.L. (2013). Youth sport: positive and negative impact on youth athletes. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 151 – 160.

- Myer, G.D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J.P., Faigenbaum, A.D., Kiefer, A.W., Logerstedt, D., & Micheli, L.J. (2015). Sports specialisation, Part 1: does early sports specialisation increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes? Sports Health, 1 – 6.

- Paul, D.J., & Nassis, G.P. (2015). Physical fitness in youth soccer: issues and considerations regarding reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Paediatric Exercise Science, 27, 301 – 313.

- Sawczuk, T., Jones, B.L., Sacntlebury, S., & Till. K. (2018). Relationships between training load, sleep duration, and daily wellbeing and recovery measures in youth athletes. Paediatric Exercise Science, 30(3), 345 – 352.

- Thomas C., Ismail, K.T., Comfort, P., Jones, P.A., Santos T. (2016). Physical Profile of Reginal Academy Netball Players. Journal of Trainology, 5, 30 – 37.

- Thomas, C., Comfort, P., & Jones, P.A. (2017). Strength and conditioning for Netball: A Needs Analysis and Training Recommendations. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 39(4), 10 – 21.

- Turner, E.T., Munro, A.G., & Comfort, P. (2013). Female Soccer: Part 1-A needs analysis. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 35(1), 51 – 57.