Youth Training - Using High or Low Repetitions for Strength – Where Should You Start?

It is now fully accepted that resistance or strength training is both safe and effective for children (5, 6) and youths (8). Regular and consistent resistance training that adheres to the progressive overload principle, has shown to increase strength greater than in natural growth (maturation) and development (7), which will benefit youths in managing high forces (as when sprinting, jumping, landing, agility), when playing sport (helping youths to be sport ready). Furthermore, strength training clearly seems to have a prophylactic quality, helping to reduce musculoskeletal injuries, especially lower limb injuries (ACL’s) (9, 13).

There are many considerations (variables) when designing an effective resistance/strength programme, for example, exercise selection, order of exercise, intensity which is related to the amount of load and repetitions performed, number of sets, which is related to the training volume (repetitions x sets), rest periods, exercise velocity, and training frequency. In a previous blog, we discussed exercise selection (Youth Training - Sport Specific Training) and how exercises can be placed on a spectrum from physical capacities to more skill based. Along with exercise selection, it could be argued that prescribing effective intensity, which is correlated with a load-repetition relationship, is an extremely important factor, especially when introducing youths to resistance/strength training.

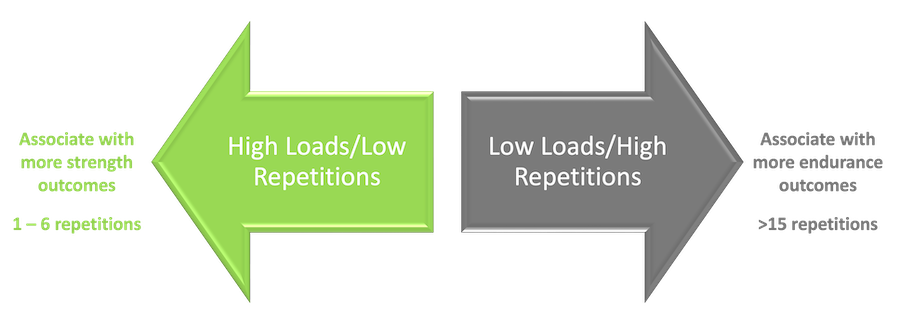

Training guidelines, for example, American College of Sports Medicine (1), suggest that novice participants should start at 8 – 12 repetitions (approximately 70 – 80% 1RM). As the participants progress in their strength and experience (technique and skill), the repetition range can widen, with repetition ranges linked to a specific training response. Generally, lower repetitions (1 – 6RM) (higher loads) are associated with strength grains, whereas higher repetitions (>15) (lighter loads) are associated with muscular endurance (14).

| Training Status/Adaptation | Repetition Range | % 1RM | Considertions |

| Novice | 8 - 12 | 70 - 80% | Untrained. No previous training experience |

| Intermediate/Advance | 1 - 12 | 70 - 100% | Wide repetition ranges that can be periodised |

| Strength | 1 - 6 | 85 - 100% | Higher loads to recruit higher motor motor units |

| Muscular Endurance | >15 | 40 - 60% | Moderate to low loads. Sub max load. |

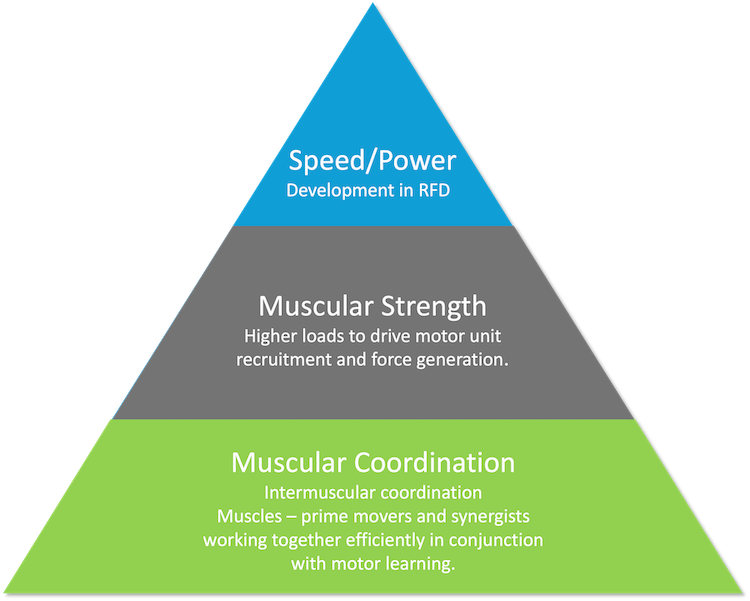

These suggested repetition guidelines are directed towards the adult population. Effective or appropriate repetition ranges for youths, may be different to adults, as factors such as, maturation and skill development need to be considered. Furthermore, there is thinking that the recruitment in muscles differ between youths and adults (5), therefore higher loads/low repetition ranges might not be suitable when introducing youths to resistance training, not just from a safety aspect, but more from a motor learning and adaptation perspective. An example, of this was shown in a study where youths were given different repetition ranges to enhance upper body strength – higher loads/low repetitions (6 – 8 reps) versus moderate loads/higher repetitions (13 – 15 reps). Interestingly, the moderate loads increased strength more than the higher loads. Higher loads (5.3%) compared to (16.3%) – another interesting point is that the higher loads training was comparable with the control group. A possible explanation for this study outcome is the challenge in disconnecting strength and muscular coordination (especially when learning new exercises and generating force in new movements). It seems that muscular coordination needs to be established before higher strength levels can be performed. This also explains why most of the early adaptations in resistance training are classified as neuromuscular (2, 4, 15).

Neuromuscular function and/or efficiency needs to be gained before trying to gain maximal strength (peak force) – higher motor unit recruitment and peak force generation, for example, higher loads (1 – 6RM) in a front squat. And it seems that there’s no shortcuts, the system needs to learn muscle synergy before high strength or forces can be generated. Therefore, by exposing youths to moderate loads (10 – 15 repetitions), this seems to be ‘enough resistance’ (passes a certain threshold) to drive coordinated adaptations – motor learning/intermuscular coordination/muscle synergies – prime movers and synergists working together (12). So, the repetition ranges for youths may look like the below figure, with moderate loads building muscular coordination. This sets a foundation for higher loads, where relative and maximal strength can be expressed. Finally, speed and power can trained, as movement velocity is probably the most transferable quality for sport and high performances (11).

Starting a Resistance Training Programme - Exercise, Repetition, Load Consideration.

When starting strength or resistance training with youths, a clear training objective is to enhance muscular coordination in a range of exercises. As we know that moderate to low loads, thus higher repetitions (10 – 15 repetitions), is enough stimulus to drive neuromuscular adaptations, and higher loads/repetitions ranges of 6 – 8, do not cause better strength improvements in beginners/untrained youths. Furthermore, using higher loads may be more challenging for the participants to learn optimal body mechanics, thus starting a resistance training programme with moderate loads should reinforce the safety and effectiveness of a well-designed resistance training programme.

Generally, coaches tend to opt for bodyweight training before adding external load (barbell, dumbbells, or medicine ball), however, the exercise selection needs to be considered relative to the overall load. For example, beginner participants may be able to easily perform 10 – 15 repetitions of lower body bodyweight exercises (squats or lunges) with many more repetitions in reserve, thus not passing a set threshold. Conversely, the same participants may struggle to perform 6 – 8 repetitions of press ups and chin ups, which are viewed as more upper body exercises. Therefore, bodyweight exercises should not be seen as an optimal starting point for beginners, including youths. The most important factor in resistance training is selecting ‘enough’ resistance to drive neuromuscular changes. Therefore, in lower body exercises, like the squat, lunges, deadlift, a moderate load are likely required so that the participants achieve a level of overload. In the upper body exercises, press ups and chin ups, these exercises may be too challenging to start with, so other upper body exercises can be selected – dumbbell shoulder press, dumbbell single arm row, or lying dumbbell bench press.

As participants perform regular resistance training, their strength levels will improve, this is likely due to improvements in neuromuscular function (muscular coordination). This change in neuromuscular function will be observed by the participant’s overall body mechanics (improvements in exercise technique), being able to perform repetitions using their starting loads, and/or having more repetitions in reserve. This first period of training is essential for the participants, and as a part of their long-term athlete development programme. It is important to understand that this first phase of training is fundamental for the participants and along with muscular coordination, other training objectives include, improvements in skills including balance (fundamental movement skills), anatomical adaptation (improvements in tissue tolerance) preparing the tissues (bones, ligaments, and tendons) for future sessions, including technical sport practice and competition.

Coach Management Portal, Resources, and Training App

As resistance or strength training is essential for the youth’s long-term physical or athlete development, getting ‘strength training or resistance training’ into their schedule is incredibly important. It has been shown that even small amounts of strength training, for example, in dynamic warm ups before PE lessons, sport training or competitions have been shown to reduce the risk of lower limb injuries, especially knee injuries (3, 10).

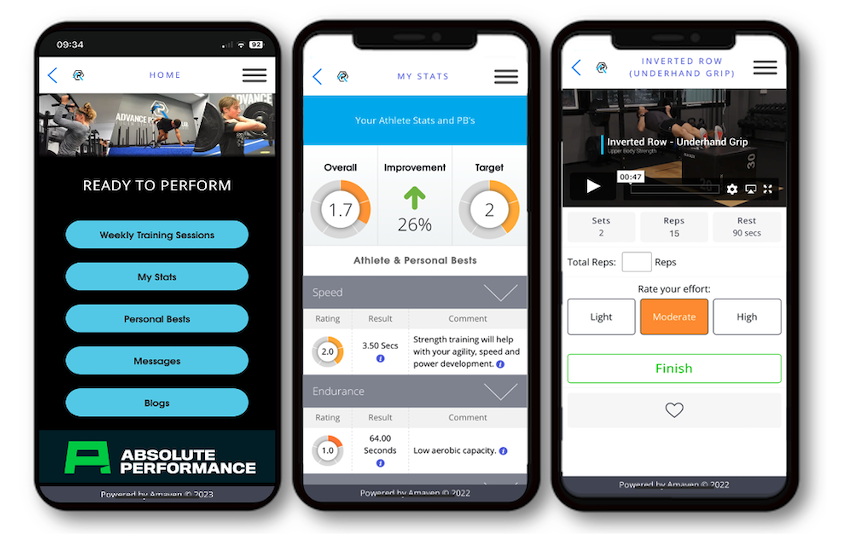

To promote strength and conditioning for youths in schools, sport clubs, academies, and for individual home training, technology has been it easy and effective for sport coaches and PE teachers to both monitor and interject strength and conditioning sessions into PE lessons and sport sessions. Our coaching portal has been created so that coaches can access a library of session plans covering a range of training modalities including, resistance training, plyometric, agility, and sprint drills. Furthermore, coaches can both test and track participants through a set battery of performance characteristics including, vertical jump, acceleration, agility, and strength (back squat), muscular endurance (press ups). Our training app has been especially created to help youths in their training and physical development. The youths can watch the exercise to learn and practice their technique. Depending on the exercise selected, the youths can upload the number of repetitions completed or the load used. Monitoring the youth’s strength (early stages muscular coordination) improvements is essential for their long-term development. By monitoring the youth’s physical development and capturing individual training loads in specific exercises, this helps the youths in selecting appropriate training loads and makes the training significantly more effective.

Practical Application

It is well accepted that resistance/strength training is appropriate, safe and effective for all youths for both health benefits and sport readiness. It is generally well-known that there is a repetition-load relationship, with lower repetitions (1 – 6) and higher loads are more associated with strength adaptations, and higher repetitions (10 – 15) with low to moderate loads are associated with muscular endurance. However, these training guidelines are directed towards the adult population, and selecting repetition ranges for youths should be based on a range of training outcomes, including, motor skill learning and strength-muscular coordination. Interestingly, prescribing heavy loads/low repetitions to youths (beginners) produced less strength gains than moderate loads with higher repetitions (13 – 15 repetitions). This training information should be useful for sport coaches and PE teachers that are interested in introducing youths to strength/resistance training. By selecting appropriate exercises, either bodyweight or loaded, youths can safely practice and learn optimal body mechanics. Furthermore, as moderate loads seem to be ‘heavy enough’ to drive neuromuscular (intermuscular coordination) adaptations, this severs as a great foundation (anatomical adaptation/injury reduction) for future periodised strength training.

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2009). American college of sports medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(3), 687 – 708.

- Anil Kumar, N.T., Oliver, J.L., Llyod, R.S., Pedley, J.S., & Radmor, J.M. (2021). The influence of growth, maturation and resistance training on muscle-tendon and neuromuscular adaptations. A narrative review. Sports, 5,59, 1 – 24.

- Asfari, M., Alizadeh, M.H., Shahrbanian, S., Nolte, K., & Jaitner, T. (2022). Effects of the FIFA 11+ and a modified warm up programme on injury prevention and performance among youth male football players. Plos One, 1 – 11.

- Cannon, J., & Marino, F.E. (2010). Early-phase neuromuscular adaptations to high-and-low volume resistance training in untrained young and older women. Journal of Sports Sciences, 14, 1505 – 1514.

- Faigenbaum, A.D., Loud, R.L., O’Connell, J., Glover, S., O’Connell, J., & Westcott, W.L. (2001). Effects of different resistance training protocols on upper-body strength and endurance development in children. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 15(4), 459 – 465.

- Faigenbaum, A.D., Zaichkowsky, L.D., Westcott, W.L., Micheli, L.J., & Fehlandt, A.F. (1993). The effects of a twice-a-week strength training program in children. Pediatric Exercise Science, 5, 339 – 346.

- Falk, B., & Tenenbaum, G. (1996). The effectiveness of resistance training in children. Sports Medicine, 22, 176 – 186.

- Llyod, R.S., Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D., Stone, M.H., Oliver, J.L., Jeffreys, I., Moody, J., Brewer, C., & Pierce, K. (2012). UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 26, 26 – 38.

- Nessler, T., Denney, L., & Sampley, J. (2017). ACL injury prevention: what does research tell us? Curr Rev Musculoskele Med, 10, 281 – 288.

- Nuhu, A., Jelsma, J., Dunleavy, K., & Burgess, T. (2021). Effect of the FIFA 11+ soccer specific warm up programme on the incidence of injuries: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Plos One, 1 – 16.

- Pareja-Blanco, F., Rodriguez-Rosell, D., Sanchez-Medina, L., Gorostiaga, E.M., & Gonzalez-Badillo, J.J. (2014). Effect of movement velocity during resistance training on neuromuscular performance. International Journal of Sports & Medicine, 35, 916 – 924.

- Santos, P.D.G., Vaz, J.R., Correia, P.F., Valamatos, M.J., Veloso, A.P., & Pezarat-Correia, P. (2021). Intermuscular coordination in the power clean exercise: comparison between Olympic weightlifters and untrained individuals – a preliminary study. Sensors, 21, 1 – 16.

- Steib, S., Rahif, A.L., Pfeifer, K., Zech, A. (2017). Dose-response relationship of neuromuscular training for injury prevention in youth athletes: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 1 – 17.

- Stone, W.J., & Coulter, S.P. (1994). Strength/endurance effects from three resistance training protocols with women. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 8(4), 231 – 234.

- Zwolski, C., Quatman-Yates, C., & Patemo, M.V. (2017). Resistance training in youth: laying the foundation for injury prevention and physical literacy. Sports Health, 1 – 8.