Reducing the Risk of Overtraining & Burnout in Youth Athletes

Even though the media and journals constantly report a decrease in activity levels in youths and a rapid increase in obesity (9), more children and younger people are playing organised sport. Moreover, extremely young children are starting to play and compete in a single sport, which may place them at risk of sport specialisation (2, 7, 11). Clearly, getting more children and young people active has numerous positive outcomes. Organised sport can also promote these positive outcomes, both physical improvements – sport skills and fitness, and social benefits, social interaction, communication and listening skills, learning rules and guidelines, being a part of a team or group. However, we do need to distinguish between general free-play activity and sport, especially when reviewing overtraining, burnout, and injuries. For example, it is very unlikely that children or young people suffer from overtraining or overuse injuries from free-play activities (5), where 30 – 60% of injuries in youths are classified as overuse-sport related injuries (1, 3). With many opportunities to join and play sports or many sports throughout the year, plus, with many offers or claims stating that an accelerated training programme can lead to high performance in youths (normally in a faster timeframe), this type of thinking will exacerbate this current trend. We need to appreciate and understand that ‘more is not always better’, especially for youths, as they are going through many changes in their growth and development – along with other lifestyle pressures, such as, schoolwork, exams, and relationships. We also need to appreciate that youths need optimal rest and recovery, alongside their general activity, training, sport practice and competition – as long-term development (no shortcuts, sudden changes in volume, or load) will reduce the risk of overtraining, burnout, and injury.

Unfortunately, it seems that there is still this idea that starting a sport at an early age and through constant practice (sport specific training and block practice) and high sport-competition, this combination will somehow give the youths an advantage in becoming elite or professional. There is simply no evidence supporting this model, on the contrary, there’s evidence suggesting that sport-specialisation is an independent risk factor to injury (4), along with the common feelings of boredom, social isolation from friends, and apathy. Thus, the most important factors regarding the youth athlete’s longevity and development, include, their health, wellbeing, engagement, and enjoyment. If we can support these factors, high performance(s) is more likely to manifest with less injuries and feelings of burnout.

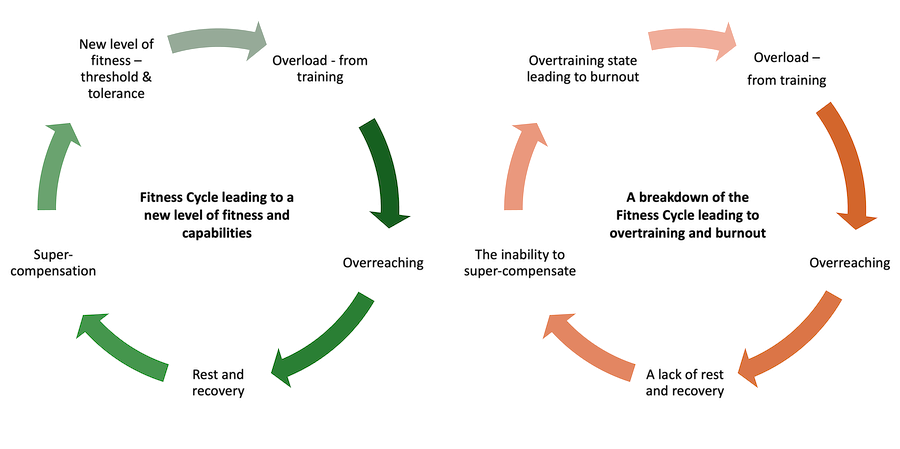

Regrettably, overuse injuries are frequent within youth sports, with 30 - 60% of all injuries being classified as sport-related/overuse (1, 3). By understanding the cycle of training compared to the cycle of overtraining, we may be able to reduce the risk of these type of injuries. Generally, the cycle of training is quite simplistic, and is grounded under the term overload. Overload is quite difficult to define, but the body has a certain or specific threshold or capability. To improve this current threshold and/or improve the athlete’s capability – overload must be applied. By applying overload to the body, through sport practice or training, the overload (stimulus) will result in overreaching, which usually manifests as a decline in performance (due to fatigue). However, through adequate/optimal recovery and regeneration, the body super-compensates (adapts) allowing the body to handle a new level of overload (stimulus). Therefore, the athlete’s fitness level has improved. Moreover, the athlete can now manage or tolerate the previous overload with less fatigue. This is the fitness model – overload – overreaching – recovery – supercompensation – new fitness level (6). However, with many youth athletes playing a high volume of sport, both training and competition, this can lead to overtraining and burnout. Simply, the fitness model is not being followed or adhered to, more importantly, the youth athletes are not resting and recovering from their sport. When falling into overtraining, and still trying to train/play sport at a high level, this will still promote overreaching, however, when in an overtrained state, the overreaching doesn’t produce supercompensation – no new increase in fitness or threshold. This pushes the athlete into a different cycle of training, with more training/sport, leading to more fatigue, frustration with their (reduced) performance. A sudden decline in enjoyment in training and sport may lead to injury and burnout. Burnout is viewed different than overtraining, with chronic overtraining leading to burnout. Burnout is frequently described as a feeling of physical fatigue, a reduced desire to train, or lack of enjoyment in training or sport competition. Unfortunately, burnout normally leads to injury and/or withdrawal, dropout from sport and activity.

| Terminology | What Does This Mean? |

| Overload | A stimulus on the body which is greater than its current capabilities and leads to a level of fatigue. Overload is required to challenge the body (systems) to gain new level of fitness. |

| Overreaching | Follows overload and refers to a possible decrease in performance or capabilities after a training cycle due to the stimulus (overload) driving to specific adaptations. Through recovery and regeneration this will lead this system to super-compensate. |

| Supercompensation | This comes after overreaching as the system is trying to reset or establish a new level or threshold of fitness (capabilities). |

| Overtraining | A possible chronic syndrome that affects function (performance), and psychological – emotions, focus, and concentration. Overtraining is associated with high volumes of training (sports training/competition) with suboptimal rest and recovery. |

| Burnout | Associated with physical fatigue and reduce motivation for training and competition. Overtraining normally leads to burnout, through the attempt to train and perform whilst in an overtrain state. |

We Need to Consider a More Holistic Approach to Youth Athlete Development and Track Wellbeing and Recovery

We certainly do not want to discourage children and youth athletes in playing sport or trying new sports. We encourage youths trying different sports, as this will reduce sports specialisation, as the youths can learn new skills and movements. Hopefully, through exploring different sports they will find a sport they enjoy and have a passion for. Furthermore, as we know that overtraining and overuse injuries are a concern for youth athletes, especially highly talented youths – as these youths tend to have more pressure to perform in many games, sometimes for different teams – school teams and club teams. As previously mentioned, we also need to distinguish between general-free-play activity and organised sport practice and competition, with coaches, parents, and staff being fully aware of the signs and symptoms of overtraining.

| Symptoms of Overtraining |

| Psychological, physiological, and hormonal changes that result in decreased in sports performance. Common symptoms include Poorer performances Severe fatigue Chronic muscle and joint pain Reduced appetite Changes in sleep patterns Personality changes - frustration and apathy Lack of focus or difficulty to concentrate Elevated resting heart rate Fatigue Lack of enthusiasm – practice or competition Difficulty in completing usual routines |

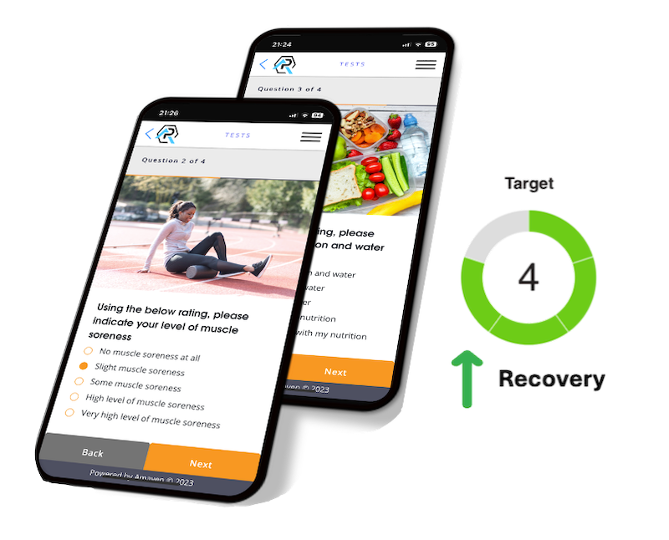

It is estimated that through good planning, management, and monitoring 50% of all overuse injuries in youths could be prevented (8). With the raise and access to technology, it is now possible to start to support youth athletes in their training, recovery, rest, and wellbeing. Through simple questionnaires and learning self-reflection, athletes can start to discover how they respond to training and what strategies help them to recover. For example, in a study by Morgan et al 1987 (10), they monitored competitive swimmers, both male and females over a ten-year-period and analysed their mood-state relative to the demands of training (overload). By monitoring the athlete’s mood-state relative to the training load, they could increase the training load whenever the athletes felt fresh and reduce when they felt tired. This simple monitoring act reduced overtraining from 10% per year down to zero.

Thus, by implementing simple questionnaires, that monitor certain aspects of the athlete’s recovery and their individual ability to respond/adapt to training, for example, feeling of readiness before training, rate your level of muscle or joint ache, sleep quality, and overall freshness from sleep – this will help both the athlete in their weekly training schedule and their coach, who can adjust their weekly training demand, signpost the athlete to complete some active rest, or promote lifestyle strategies – nutrition, rest, sleep to promote recovery and regeneration. In conjunction with questionnaires and monitoring of the athletes, studies have published guidelines on reducing the risk of overtraining. These include (2, 8).

- Training should be interesting, varied, and age appropriate.

- Allow for 1 – 2 days per week, away from organised sport. Try other general activities

- To reduce sport specialisation, take 2 – 3 months off away from organised sport and competition. Use this time for general strength and conditioning.

- Monitor any increase in training volume or intensity (gradual increases/ max of 10% per week. A ~5% weekly increase is probably a better strategy).

- Focus on wellbeing on the athlete. Promote and encourage the athletes to self-reflect and ‘listen’ to their bodies.

Summary – Understanding the Long-term Goal with Youth Athletes

By encouraging the athletes to frequently monitor and track both their training loads and recovery (athlete-centred approach) the athlete’s overall training (training cycle) will organically become more individualised, as everyone will respond differently to the same training; remember we also need to appreciate other aspects of life stresses – school, exams, relationships, nutrition, and sleep into the mix, as these factors will affect recovery and adaptation.

Unfortunately, overtraining, burnout, and overuse injuries are extremely commonplace in youths, especially in talented youths, and/or youths playing or performing endurance- high volume sports. It has been suggested that 50% of overuse injuries can be prevented through good planning, management and monitoring. Furthermore, simple guidelines have been recommended to reduce overtraining and injuries – replacing the idea of more is better!

Coaches, parents, and staff need to understand the difference between general activity, general training, sport practice, and competition. Most guidelines are suggesting that athletes take 2 – 3 months off away from their sport. This 2 – 3 months can be used productively through general strength and conditioning training, building and developing general physical capacities and motor skills. As strength and conditioning training can be micro-dosed and is disconnected from their sport (indirect transfer), this will enhance sport preparation and reduce any risk of overtraining (overuse injuries).

By being fully aware of the signs and symptoms of overtraining and encouraging athletes to track their recovery, including, readiness, energy levels, muscle and joint ache, sleep quality, and freshness after sleep - optimal guidance can be provided allowing youths to develop into well-rounded healthy and robust athletes.

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Baxter-Jones, A., Maffulli, N., Helms, P. (1993). Low injury rates in elite athletes. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 68, 130 – 132.

- Brenner, J., & The Council on Sports Medicine & Fitness, American Academy of Paediatrics. (2007). Overuse injuries overtraining, and burnout in child and adolescents. Paediatrics, 119, 1242 – 1245.

- Dalton, S.E. (1992). Overuse injuries in adolescent athletes. Sports Medicine, 13, 58 – 70.

- Feeley, B.T., Agel, J., & LaPrade, R.F. (2015). When is it too early for single sport specialisation? American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(1), 1 – 8.

- DiFiori, J.P. (1999). Overuse injuries in children and adolescents. The Physician & Sports Medicine, 27(1), 75 – 89.

- Hollander, D.B., Meyers, M.C., & LeUnes, A. (1995). Psychological factors associated with overtraining: Implications for youth sport coaches. Journal of Sport Behaviour, 18(1), 3 – 22.

- Jayanthi, N., Kleithermes, Dugas, L., Pasulka, J., Iqbal, S., & LaBella, C. (2020). Risk of injuries associated with sport specialisation and intense training patterns in young athletes. A longitudinal clinical case-control study. The Orthopaedic journal of Sports Medicine, 8(6), 1 – 12.

- Johnson, J.H. (2008). Overuse injuries in young athletes: cause and prevention. National Strength & Conditioning Association, 30(2), 27 – 31.

- McDermott, L. (2007). A government analysis of children at risk in a world of physical inactivity and obesity epidemics. Sociology of Sports Journal, 24, 302 – 324.

- Morgan, W.P., Brown, D.R., Raglin, J.S., O’Conner, P.J., & Ellickson, K.A. (1987). Psychological monitoring of overtraining and staleness. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 21(3), 107 – 114.

- Post, E.G., Trigsted, S.M., Riekena, J.W., Tetxel, S., McGuine, T.A., Brooks, M.A., & Bell, D.R. (2017). The association of sport specialisation and training volume with injury history in youth history. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(6), 1 – 8.