What Does it Take to Develop as a Youth Athlete?

The youth athlete’s schedule is usually extremely demanding with school, studying - potential exams quickly approaching, navigating a host of relationships, along with sport practice, and sport competitions/competitive games – frequently 2+ sports. We know that stress (stress here is thought of as situations that may be out of the control or management of the young athlete, which is different to mechanical stress) may influence and increase the risk of injury/reduce sport performance – additionally, if the athlete does become injured this frequently affects their identity and overall confidence (9). Along with this, the youth athlete is also coping with maturation, growth, and development. With all this demand on the young person, we need to think clearly and wisely about their long-term development, as the number one priority, is the athlete’s physical preparation, overall health, and wellbeing.

To help with injury reduction and physical preparation, Merkel (2013) (7), offered clear strategies including, sport readiness, aerobic and anaerobic fitness, strength training, flexibility, proper rest, proper hydration, and proper nutrition. If we take a closer look at these key factors, this helps to create a well-defined athlete plan, which closely aligns to a long-term athlete development framework (2).

| Athlete | Why this is important for the youth athlete |

| Sport Readiness | Athlete preparation. Anatomical adaptation. Sport normally consists of high forces that athletes must cope with - sporting demands. |

| Aerobic and anaerobic fitness | Having a solid aerobic foundation. This can be from free-play, general activities, conditioning, and the actual sport - practice/competition. |

| Strength training | Free-play in young children transforms into more structured strength training. Strength training can develop both physical capacities and general motor skills. |

| Flexibility | Some youth athletes may lose range of motion and/or coordination through their maturation. Enhance flexibility/range of motion via strength training activities - range of motion where force is applied. |

| Proper rest | Sleep, bed-time, active recovery, down time for growth and repair. |

| Proper hyrdation | Clean quality water. Reduce sugary and energy drinks. |

| Proper nutrition | High quality food (less focus on calories) - high dense nutrition for energy availability, growth, repair, and development. |

By creating and having a long-term plan, we can start to prioritise specific areas of fitness to help each athlete develop whilst staying healthy and robust. Furthermore, we can also support athletes in reducing the risk of falling into sport specialisation – with sport specialisation being viewed as to succeed in sport and to play at the highest level, the child needs to adopt that sport from an early age and practice/compete throughout the year (6). We are not completely sure that sport specialisation – year-round training and performing in one sport – leads to injury, but there is evidence that it does significantly increases the risk (13) – for example, in a study reviewing 1206 seven to eighteen-year-old athletes, by selecting one sport for 3 years, sport specialisation was reported as an independent risk factor (1). Moreover, training, playing, and focusing on one sport could lead to frustration, burnout, and lack of personal enjoyment within youth athletes (4).

Use Your Training Time Effectively – How to get the Most Out of Your Training

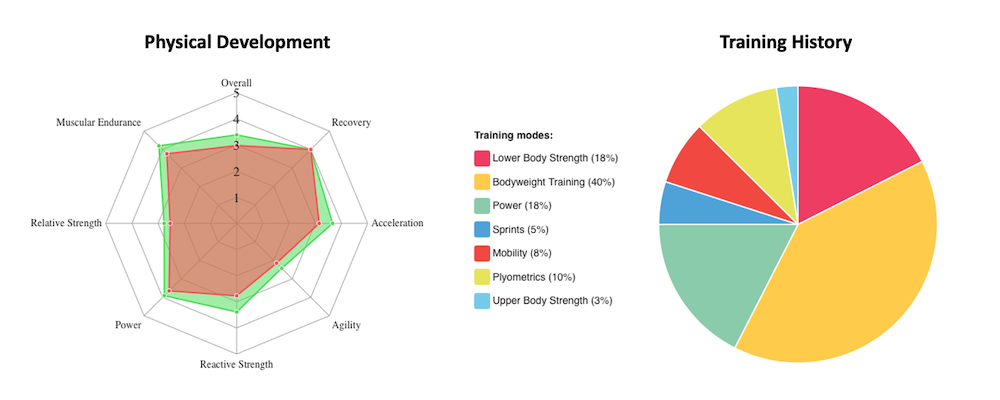

As previously stated, youth athlete’s time is limited, as factors include parent availability, transport, and time away from their sport practice, competition, and other school commitments. These time constraints may explain why we see a general lack of sport or physical preparation. Physical preparation can be defined as weekly training to develop specific physical capacities, and unfortunately, a lack pf physical preparation was identified as a major risk factor, in this case for female netball players (3). Therefore, as time is limited with youth athletes, it is essential that athlete’s physical capacities (10) and general wellbeing are tracked and monitored (14), for example, strength, acceleration, vertical jump, change of direction/agility, reactive strength, recovery, sleep, muscle soreness, and energy levels. Through regularly testing and monitoring, this helps to create a baseline of their physical capabilities and identifies areas of fitness or lifestyle to focus on. This is why physical testing or monitoring should not be viewed as a pass or fail or even ‘fitness tests’, but rather the information is building an athlete profile. By creating an athlete profile this empower each athlete to review their baseline capabilities relative to their sport, track personal bests in lifts and plot and amend short and long-term goals. This clearly gives the athlete confidence in that they are being supported, furthermore, the athlete understands their next of block training to aid in their physical preparation, plus, lifestyle choices to support recovery and wellbeing.

In a recent blog, we discussed the difference between physical capacities and skills, and how it can help with exercise selection – you can read that blog here. In summary, to drive physical capacities the exercise needs to be loaded effectively, where skills are an expression of force x coordination (inter/intra-muscular coordination) x speed. Again, by creating an athlete profile, this aids in effective exercise selection in driving a physical capacity or skill (remember there will also be an overlap with these qualities).

Generally speaking, with young athletes, many of them have been exposed to some skill development, from general activities and playing their sport, thus it could be argued that their physical capacities need to be targeted, for example their relative strength, so simply prioritise strength training in their weekly training! – which is consistent with Merkel’s list of injury risk factors. Strength training can sit in both ends of the capacity/skill spectrum, but remember that if you can load the exercise, this will normally drive more capacity type adaptations, where if the exercise is performed quickly (less external load), this will lead to more skill and coordination.

A major challenge with regular strength training is equipment availability - There are simple answers, if possible, join a gym, especially a gym that has coaches with a strength and conditioning background. Alternatively, grab some home-equipment, for example, a set of dumbbells, kettlebell, and a medicine ball. If equipment or gaining access to a gym is a challenge, training at home with dumbbells, kettlebell, and/or a medicine ball is still hugely effective, especially if new to strength training. Example of exercises can be goblet squats, lunges, Romanian deadlift, single leg deadlift. Furthermore, this type of training would fall into integrative neuromuscular training – which is linked in reducing sport-related injuries (through better athlete preparation) (8).

Home strength training will have significant benefits to the athlete’s physical preparation, so the athlete should be encouraged to focus on this area. However, as the athlete develops their strength and movement strategies, completing more repetitions is not recommended as this will increase the athlete’s training volume. At this stage of development, as the athlete has increased their training age, it’s now time to find a local gym - The trick here is to monitor and track the athlete so we can use the athlete’s time effectively – athlete-centred approach.

Summary to Prioritise Your Training

| Don't think or train muscles in isolation | Think movements and/or load. By using a range of lower body and upper body exercises, all muscles will be effectively trained. |

| Prioritise your physical capacities | As time is usually limited focus your training on developing your strength, as skill development (and conditioning) will come from playing your sport. |

| Track your development | Use the Athlete App to track your personal bests, load lifted, repetitions completed, exercises and training modes. Get in the habit of keeping a training journal, as this will help with overall recovery and athlete wellbeing. |

| Small steps | Welcome and recognise small steps and improvements - this can be personal bests, your recovery, your eneregy levels, and generally how you feel. |

Growing the Athlete’s Training Age – How This Will Affect Your Training

As athletes mature and develop, their sport demands also increase, so it is essential to start their strength and conditioning training as early as possible. By overviewing a hypothetical case study, this can demonstrate how the athlete’s training age will affect their physical training. Young children, pre-post height velocity, should be active through free-play, general activities, self-discovery, and be introduced to some sports for personal development. From the young child being exposed to this variety of activities, movements, and sports, this will help with general motor skills, movement strategies or movement skills, and coordination (12). At this early development, coordination can be viewed as strength-coordination, as the system is learning to express force mostly through neuromuscular adaptations (11) – this will be observed by the child’s movement skills, balance, coordination, and agility – all improving.

Even though the child has been active, learnt and developed their movement skills, and may be playing multi-sports, their training age is still zero – training age can be thought of as the number of years the youth has regularly and consistently being involved in strength and conditioning training. As the youth is introduced to a strength and conditioning programme potentially around peak-height velocity, this will start the clock on their training age. Having a low training age, will place the youth as untrained, which basically means that the system will need less stimulation to drive training adaptations. In other words, there’s lots of training potential! Therefore, they may start with bodyweight strength training, squats, lunges for lower body, and medicine ball overhead press, and dumbbell bench press for upper body. Again, refer to our sport specific training blog for more information.

As the athlete is new to strength training (low training age), they may only need one – two sessions per week, with a relatively low load (overload – bodyweight or 50 – 70% 1RM), but their training volume may be relatively high, due to the number of repetitions and exercises (5). Training load and volume tend to be inversed, with training load starting low. This allows the athlete to practice the lifts, additionally, performing more repetitions may also help with learning effective movement strategies.

If the athlete is consistent with performing strength training (1 – 3 sessions per week, average 2 sessions per week), they will gain positive adaptations, further neuromuscular adaptations, again, this may be observed with better form/technique – with the athlete stating that the ‘load’ is feeling light. This is due to that fact that the athlete’s training age is growing. It is difficult to state when a youth athlete ‘grows’ out of being untrained - is this down 12-months of strength training or hitting a strength metric i.e. relative strength ratio or number of pull ups? I would argue a mix of both!

As the athlete’s training age grows, their training needs to grow with them. This can only be achieved by keeping clear training history and data – for example, exercises, repetitions, number of sets, and load lifted. This information will benefit both the athlete and coach through effective programme design – and helping the athlete to improve their physical capabilities in preparation for their sport practice and competition.

Summary

Youth athletes have a demanding time schedule, with limited time for physical preparation due to school, exams, sport practice and competition commitments. Unfortunately, many youth athletes fall into sport specialisation thinking that playing one sport will lead to higher performances – this frequently leads to injury, burnout, frustration, and low enjoyment. As time is limited, we need to prioritise physical preparation with our athletes and use long-term thinking with their development. For the first time, due to technology and access to information, we can start to track, monitor, support, and give guidance to more athletes and their parents on physical development for sport preparation – building individual athlete profiles.

Through regular tracking and monitoring of the athlete’s physical capabilities – strength, speed, power, agility, reactive strength – this can inform the coach on the training that the athletes need. This also helps to identify effective (and time efficient) exercise selection. Furthermore, having a clear picture of the athlete’s training age, the athlete can perform the minimal training dosage – for example, 1 – 3 strength training sessions per week. This minimal dosage allows the coach to change the athlete’s programme as they develop, and as their training age grows. This is key to long-term athlete health, wellbeing, and sport performance.

Youth Strength & Conditioning Platform for Schools, Sport Clubs, and Academies.

Our platform helps to deliver effective training and tracks athletic progress and development, with the core objectives of reducing the risk of injuries and to promote both sport readiness and performance. The platform’s features include -

- Strength and conditioning tests and dashboard to monitor and compare athlete metrics

- Athlete app - athletes can discover new exercises and train independently

- Track data - monitor athlete’s training loads, RPE, and training adherence

- Reports - simply create squad, team, and individual athlete reports

- Full curriculum - follow a strength and conditioning curriculum with a library of session plans

References

- Feeley, B.T., Agel, J., & LaPrade, R.F. (2015). When is it too early for single sport specialisation? American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(1), 1 – 8.

- Ford, P., De Ste Croix, M., Lloyd, R., Myers, R., Moosavi, M., Oliver, J., Till, K., & Williams, C. The long-term athlete development model: physiological evidence and application. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29)4), 389 – 402.

- Gamble, P. (2012). Physical preparation for netball – part 1: Needs analysis and injury epidemiology. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 22, 10 – 15.

- Giusti, N.E., carder, S.L., Vopat, L., Baker, J., Tarakemeh, A., Vopat, B., & Mulcahey, M.K. (2020). Comparing burnout in sport-specialisation versus sport-sampling adolescent athletes – a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 8(3), 1 – 7.

- Lloyd, R.S., Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D., Stone, M.H., Oliver, J.L., Jeffreys, I., Brewer, C., & Pierce, K. (2012). UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. UK Strength & Conditioning Association, 26, 26 – 39.

- Malina, R.M. (2010). Early sport specialisation: Roots, effectiveness, risks. Curr. Sports Med Rep, 9(6), 364 – 371.

- Merkel, D.L. (2013). Youth sport: positive and negative impact on young athletes. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 151 – 160.

- Myer, G.D., Faigenbaum, A.D., Ford, K.R., Best, T.M., Bergeron, M.F., & Hewett, T.E. (2011). When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep, 10(3), 155 – 166.

- Nippert, A.H., & Smith, A.N. (2008). Psychologic stress related to injury and impact on sport performance. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Clinics of North America

- Oddsson, H.R. (2019). Athlete profile: basic anthropometry, physical fitness and specific skill of the Icelandic female youth national teams. https://hdl.handle.net/1946/31272, 1 – 149.

- Paster, A.S., Garcia-Sanchez, C., Nieto, M.M., & de la Rubia, A. (2023). Influence of strength training variables on neuromuscular and morphological adaptations in prepubertal children: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 20, 1 – 24.

- Roach, L., & Keats, M. (2018). Skill-based and planned active play versus free-play effects on fundamental movement skill in preschoolers. Sage Journals, 125(4), 1 – 9.

- Ruedi, G., Schobersbergerm W., Procecco, E., et al (2012). Sport injuries and illnesses during the first Youth Winter Olympic Games. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(15), 1030 – 1037.

- Temm, D.A., Standing, R.J., & Best, R. (2022). Training, wellbeing and recovery load monitoring in female youth athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 19, 1 – 21.